General Soil Health_SSK_11_08_23

Overview

Soil health is defined as the capacity of soil to function as a vital living system that sustains productivity, maintains environmental quality, and enhances plant and animal health (Doran and Zeiss, 2000). Soils carry out five essential functions to achieve this:- regulating water infiltration and movement;

- sustaining plant and animal life;

- cycling and storing nutrients;

- filtering and degrading pollutants; and

- providing physical stability and support (USDA-NRCS, 2023).

Soil fertility and soil quality are terms sometimes used interchangeably with soil health, although these concepts typically pertain to more localized functions within a specific economic framework. Soil fertility is the capacity of a soil to support plant growth and crop productivity. Soil quality includes chemical and physical properties (like pH, texture, and water holding capacity) and reflects the ability of soil to function within a specific agricultural or environmental context. Soil health encompasses functions with broader impacts, even at global scales. In addition to enhancing agricultural productivity, soil health benefits also include reducing greenhouse gas emissions, mitigating climate change, and supporting recreational and cultural activities.

Management Recommendations

Management practices including high disturbance tillage, repeated monocropping, and intensive fertilizer and pesticide use can threaten soil health. These activities often accelerate soil erosion and leaching of agrochemicals into water bodies, negatively impacting water quality. Intensive management can also elevate disease pressure and diminish soil’s ability to withstand environmental and climate stress. Conversely, maintaining healthy soils can reduce dependence on synthetic chemical inputs, human labor, and farm machinery usage. By maximizing soil health, we can not only support economic productivity but also conserve water, air, and environmental quality.

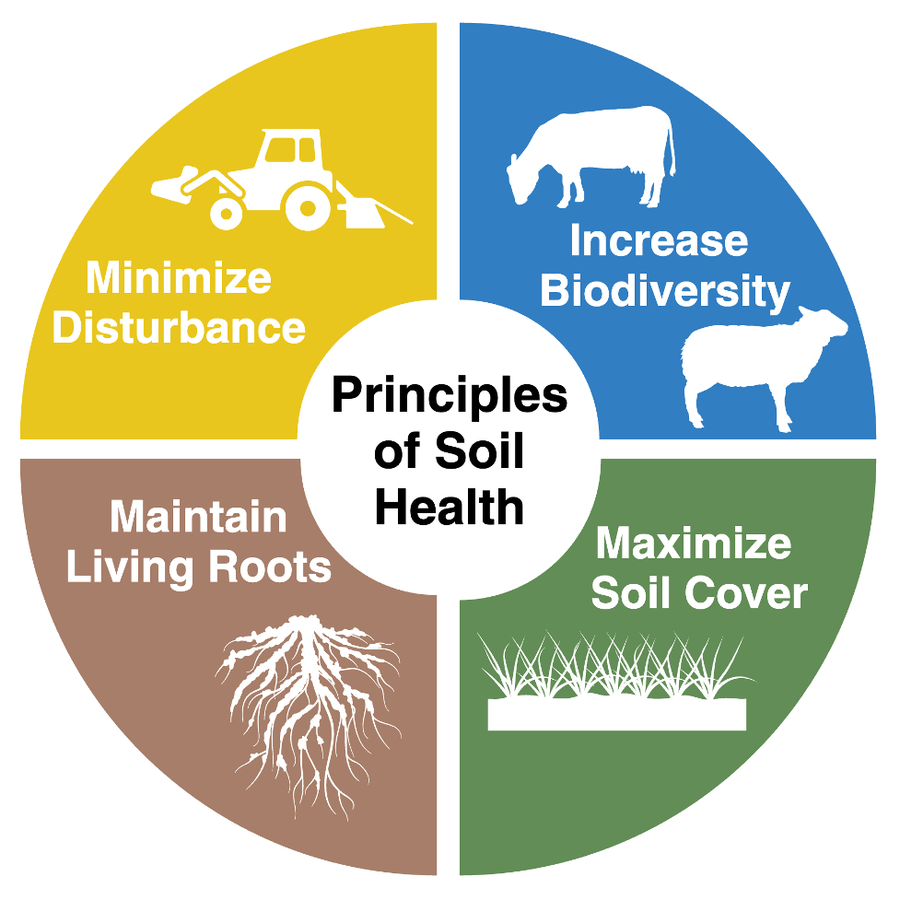

The USDA-NRCS recommends four general principles for maintaining soil health and improving soil function:

Farmers can follow these principles by adopting management practices like crop rotation, cover cropping, conservation tillage like no-tillage or reduced tillage, integrated crop livestock systems, and optimized nutrient applications. For example, maximizing soil cover with living (cover crop) or decomposing (compost) plant residues can stabilize soil particles thereby reducing erosion and soil crusting while also promoting crop germination and emergence. Implementing year-round rotations with cash and cover crops keeps living roots in the soil which can increase soil carbon. Roots release carbon-rich exudates that serve as food for beneficial microbes, increasing their abundance and activity. Heightened microbial activity, coupled with minimized soil disturbance, favors stable aggregate formation and improved soil structure. Well-structured soil with adequate pore space can enhance water infiltration while reducing compaction and erosion. Importantly, it is essential to understand these principles within the context of your land and agricultural production system. This contextual understanding is critical for practical and relevant land stewardship.

Assessment Tools

Laboratory testing of soil health indicators can help evaluate current soil health conditions, recognize constraints, and identify new management strategies. Soil health indicators are measurements that predict specific soil health functions. While numerous tests are available, none are universally accepted. Connect with your local NC State Extension Agent or Specialist to identify an assessment strategy that supports your soil health goals and that is relevant to your production system.

The USDA-NRCS has developed a soil health and management assessment framework (SMAF) (Andrews, 2004) ,which measures primary indicators of soil health. The Soil Health Institute recommends three measurements for assessing soil health: 1) Soil organic carbon concentration, 2) Carbon mineralization potential, and 3) Aggregate stability.. There are a number of independent soil health testing labs which offer a variety of evaluation metrics and interpretations. These include the Cornell Soil Health Laboratory’s Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health (CASH) and the Haney Test. In addition, the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services offers free soil testing (April-November), and Soil Test Reports include pH and nutrient analysis. For more information on physical, chemical, and biological aspects of soil health, explore additional resources available here in the Soil Health and Management extension portal.